Note: I should have probably posted this two weeks ago, but I was still working things out when it came to Substack alternatives. I may still have more to do, but…here we are, the promised response to Yann LeCun’s December 31st/January 1st tweets. Working now on some horse blogs, as well as writing blogs.

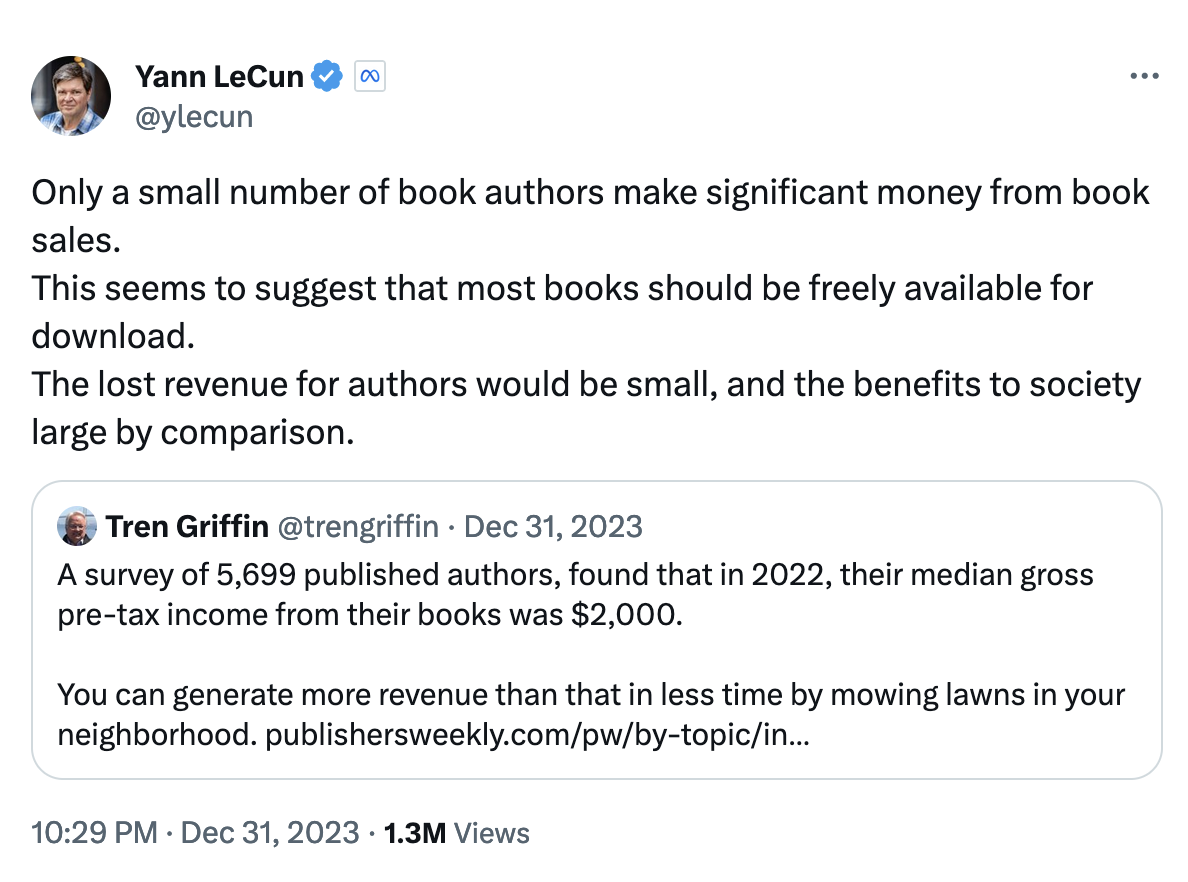

One of the not-so-delightful parts of New Year’s Day 2024 was a series of postings by Yann LeCun (chief AI scientist at Meta) on Xitter saying that most book authors should release their books for free, because…oh, here’s the screenshot.

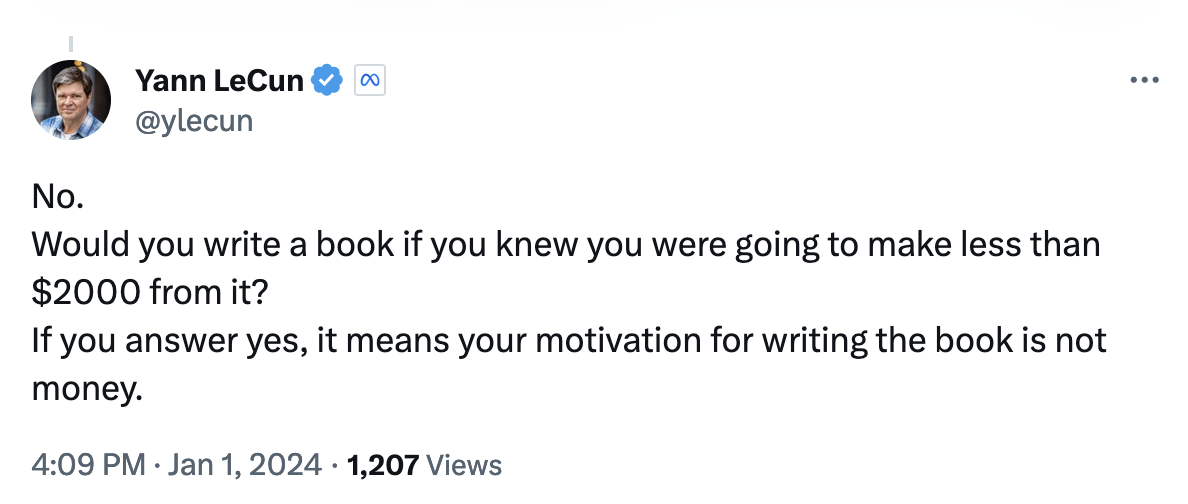

Needless to say, that sentiment didn’t go over well with a number of authors, including me. And because it was New Year’s Day, many of us had some time to express our opinions. LeCun kept focusing on the low dollar amounts most authors make as a justification for making their books available for free downloads, and that if authors aren’t expecting to make a lot of money off of their work, then they are motivated more by intellectual impact. Ergo, they should release their work for free if that is the case.

Sigh. Yet another example of how low the “information wants to be free” argument has devolved. LeCun’s argument has a number of flaws, including the reality that no one in publishing, including publishers, can tell you in advance whether a book is going to be a hit with the public or not. Oh, there’s a certain amount of sales that can happen given the right amount of money spent on promotion.

However, there is no tried-and-true formula for discerning what books will sell well. If there is, New York has yet to discover it. The same holds for a number of ambitious and aggressive self-published writers.

Granted, one has to keep in mind that LeCun is coming from an academic perspective and he is most likely thinking of nonfiction. Even at that, however, it’s somewhat saddening to read the implied notion that one either writes for intellectual impact or money (and the manner in which he repeatedly frames the argument as either/or strongly suggests he’s operating from a nonfiction point of view). There’s no room for entertainment or education (which I suppose could loosely be defined as “intellectual impact”) in this framework.

However, most of us who write, especially fiction, are not doing so as part of a day job. LeCun comes from an academic background where publication, either for free or requiring the author to pay for it, is part of the job requirement. He can afford to give away his creations because he’s already receiving compensation for them through his work. LeCun’s bias shows up in his own words:

Those of us who write fiction, whether we’re submitting to traditional publishing or self-publication, start laughing bitterly at this statement, because we don’t know how much we’re going to make from it unless the book is already under contract. This current work-in-progress could manage to hit the popularity-go-round on release—catching the wave of what’s currently popular. Or a major influencer on BookTok or other online venue suddenly discovers the book and promotes the heck out of it. Or…lots of possibilities exist, including the possibility that this book becomes a sleeper hit months or years after initial release.

The reality is that unless you have an advance in hand before you start writing the book (more common in nonfiction than fiction) you just won’t know before publication whether the book is a hit or not. That’s just the reality of publishing.

But let’s also look at the other piece of LeCun’s argument…the “intellectual impact” and “benefits to society” side. Again, this is more of a nonfiction writer’s position. “Intellectual impact” might fall more to the literary side, where the author is engaged with dialogue about theme. “Benefits to society”—I suppose that depends on how one approaches the concept of entertainment as either a frill or necessity.

That said, most fiction writers are writing to tell a story, with the primary purpose of entertainment, whether that be for the author or for the author’s hoped readers.

Then the question becomes, how does society benefit from free entertainment? Oooh, that’s a monstrous can of worms to consider, especially after all the years of apparently “free” entertainment provided by broadcast television and radio. Only said entertainment was not exactly “free.” Those radio and television shows had/have sponsors, advertising, and product placements within the story framework. “Free” periodicals have donors, advertisers, and sponsors.

And shall we discuss pop-up ads on websites?

The reality is that there is no such thing as “free” information. Someone pays for the creation and the distribution of such information, and someone pays for the receipt of such information. The purpose for the existence of such information can range from any sort of combination of product advertising to sharing a cool idea to entertainment to promotion of particular ideologies.

No matter what the purpose, at some point payment happens for the creation of the concepts, images, and words, both by the creators in the form of the efforts they perform (for which they will receive some sort of compensation, either by an employer or by selling the result of their creative endeavor) and by the recipients in the form of paying for the product through purchase, subscription, or exposure to advertising/ideologies.

It’s not free, to either creator or recipient of information. It only seems as if it is free.

And so, to return to LeCun’s assertion that most books should be freely available for download, I assert that his conclusion is based on a flawed assumption that information wants to be free. That the spread of information, whether through fiction or nonfiction, is free.

I assert that all information is paid, whether through effort or money. LeCun and others who assert information wants to be free conveniently overlook the cost of the effort it takes to create something.

Information doesn’t want to be free. It just makes you believe that it wants to be free.